Malaika Cheney-Coker was born in Nigeria and spent her early years there, as well as some time in the Philippines with her maternal relatives. She later moved to Sierra Leone, where she spent the rest of her childhood. In this Q&A, we discuss her Sierra Leonean roots, the themes explored in her book, and her hopes for the future.

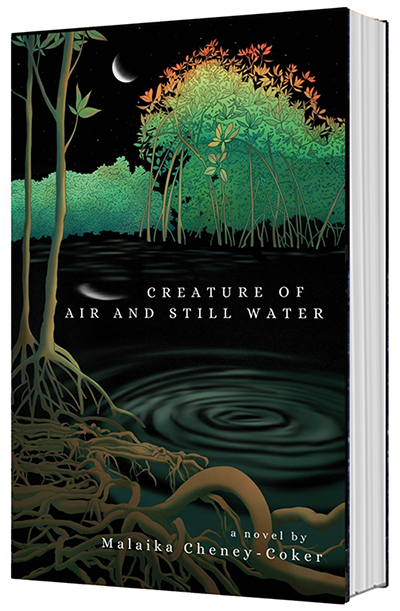

1. What inspired you to write Creature of Air and Still Water? Was there a specific event or idea that sparked the story?

I’ve always wanted to be a writer, so from childhood, I dreamed of writing novels. I even pursued an English degree, Literature concentration, to help get me on that path. But it wasn’t until several life events in my twenties that I felt I had the emotional depth, and the inspiration for my main character, to take the plunge. Seth’s journey explores grief, identity, and mental health.

2. These are quite topical issues. Any particular reason why were these themes important for you to address in this novel?

Fiction writers typically don’t set out to address topical issues. They have a character or characters in mind, struggling with x or y life circumstances, or some kind of story idea begging to come to life. And then the topics kind of come secondarily to that. For me, there was the driving question of “What happens when someone has everything and then suddenly decides to give it all up? What would lead a person to such a drastic decision that no one else around him understands?” And so in trying to answer that question, the background around Seth and his family’s unprocessed grief, mental and spiritual issues, etc, emerged. I have to say too, that having lost my mother just a few years before starting the novel, the issue of grief and what an earthquake it was certainly was quite consuming for me. So in a way, I am contradicting myself — there was a part of me that said, “I have to give voice to this process which obliterates life as we know it –the experience of losing a loved one.”

3. Being born in Nigeria and having spent part of your childhood in the Philippines and Sierra Leone. How did this background help shape your approach to this novel?

It’s given me a cultural fluidity and ability to switch perspectives that I think has helped in my writing. When you have the kind of background I do, you’re always going to be just that little bit odd, no matter where you are, but that can also be a strength. Unlike me, Seth is not bi-racial and does not have to straddle cultures in the same way. However, as one of many who’ve emigrated from Sierra Leone, he does have to face the question of where he belongs, where home is. And in him doing so, I was also exploring my own feelings of plurality, which is to say, I think I am more comfortable than most with the idea that you don’t have to only be one thing or belong to one place. Our identities can be complex and grow even more complex over time.

4. What was the most challenging part of writing the book, and what part flowed most naturally for you?

The technical aspect of writing was definitely the most challenging. I found out the hard way that novel writing is a craft, and any level of mastery requires immense training. There are different ways you can go about it, which in my case was reading lots of books on how to write, doing seemingly endless drafts till my early readers didn’t lose interest in the story halfway through, getting a professional manuscript critique, etc. I would say fairly unique to the craft of writing literary fiction is also the emotional energy required to execute the story. This is because imagination and creativity require energy and also, you have to allow yourself to feel what your characters are going through, in order to write their stories well. There were some years that due to the emotional energy output my own life circumstances required, I did not have any leftover energy to write at all.

Finally, you cannot be in any old mood and sit down to write and expect anything worthwhile to come out. So, I also had to learn to cultivate “the muse” and adjust my expectations at times when it was clear inspiration would not be forthcoming.

What flowed most naturally for me was writing sentence-level prose that sounds like poetry. I’ve always gravitated towards lyrical, poetic prose in other writers and I wanted to write the kind of book I would enjoy reading. Hopefully, all my years of writing poetry, whether good or not, paid off.

5. How do you view mental health and various cultural interpretations of such illness?

One of the catalytic questions in the book is that while Seth is diagnosed with a mental illness at the start, he refuses to accept that diagnosis, leaving the reader to wonder whether they should side with his psychiatrist or with Seth. Without giving too much away, the book does question modern psychiatry’s role in diagnosing and treating some mental and spiritual states that seem aberrant, and opens the door to exploring what ancient traditions or religion have to say about the matter.

6. How has your Sierra Leonean heritage influenced your storytelling style or voice as a writer?

To some degree it’s imbued me with a sense of responsibility to situate the individual and family stories in the broader context of history and contemporary politics, in order to educate Western readers. So, I had to be aware of how slavery, colonialism, immigration, and the recent (at the time of the opening of the novel) civil war had affected the characters’ lives and weave these considerations into the story organically. At the same time, the last thing I wanted was for my novel to perpetuate tropes about poverty and war in Africa. For me, it wasn’t about negating these conditions but rather, providing balance. So, nearly all of the characters are Sierra Leonean, and so I hope the reader can intimately feel the peculiar, tragic, and beautiful experience of being Sierra Leonean through their lives.

7. What are you hoping readers in Sierra Leone might take away from this book, versus readers elsewhere?

I was just at a book reading yesterday moderated by a dear Sierra Leonean friend and attended by other Sierra Leoneans. The questions and reactions I got from her and others were exactly what I’d hoped for — being able to relate to descriptions like stoning mangoes from trees, or eating bread and akara, the honey man going around selling honey in the middle of the day, and overall, the “sensory haven” as she called it, that is Freetown. I also hope my Sierra Leonean readers get a chance to reflect on some of the deeper themes and topics in the novel. As a fiction writer, my job isn’t to tell people how to feel or think but to provide them with some fodder to examine their own beliefs and experiences. For example, one topic we discussed yesterday is the tendency, in many Sierra Leone families, to not talk about loss or tragedy, thereby denying children, especially, the ability to process the event and move on. You see this strongly in the Walker family and also see some of its origins in Evelyn’s family, which shows how such a practice can have generational consequences.

Finally, as Seth of course sets up a camp for underprivileged kids in Freetown, we talked quite a bit about how we can best serve our young people and what are the risks and necessities of opening their horizons to professions beyond the “respectable” ones.

8. Did writing this book make you feel closer to Sierra Leone? Or help you examine issues you hadn’t done for a while?

It certainly made me feel closer to Sierra Leone! There’s another element to it, which is that every human wants attention — to be seen, heard, validated. The opportunity to capture in print and for posterity, some of the good and bad of the experience of being Sierra Leonean, was a true privilege for me. As a work of fiction, the story is by no means a mirror of my experiences but one that I hope is universal enough to appeal to Sierra Leoneans and non-Sierra Leoneans alike. With such a multi-cultural background.

9. Where do you consider home?

Home is wherever my family is — my husband and two sons — which is currently Atlanta, a city I’ve grown to love over the past 25 years. Home is also Freetown, which I still deeply miss, and which feels like home in my heart of hearts. At the same time, much as I love my Sierra Leonean relatives, when I consider where I have the most extensive family ties and where I have also been loved and nurtured, it’s the Philippines, especially my grandparents’ house in Dumaguete. Thankfully, I’m also blessed to have several of my Filipino cousins and their families here in the States, which has, over time, become a new home for the Lim family.

10. Your dad also being an accomplished writer, did you draw any inspiration from his style or notice this writing influence on you?

I did draw quite a bit of inspiration from his style, which is about the most profusely elaborate and imaginatively rendered prose I’ve ever come across. In addition to being a novelist, he was first a poet, and some of my own poetic sensibilities must have been influenced by, or inherited from him. While my style is quite different, I took away from his writing a sense of what’s possible in prose and in writing culturally-situated fiction. Finally, I imbibed my sense of Krio heritage from my dad, some of which made it into my novel just as he has woven that heritage quite prominently into his writing.

11. Any advice for aspiring writers in Sierra Leone and across West Africa?

It’s hard for me to say, as I don’t know the literary scene in Sierra Leone or West Africa, not having lived there for so long. I can give more general advice though, which is to have unshakeable faith in the story you’d like to tell. Those of us growing up in places like Sierra Leone saw far too few books written by people that look like us or were situated in societies like ours. As a kid, most of the stories I read had references I could barely relate to — longing for more sunlight in cold weather, eating strawberries and cream, etc. No matter where you come from, trust that your stories are as vibrant and fascinating as any, all they require is for you to acquire the skill to tell them well.

12. Are you currently working on another project or book? What can we expect next from you?

The rude surprise awaiting many writers is that marketing a book is also a lot of work, so that is the focus at the moment. However, I do have two, possibly three other novels in mind. Thankfully, having learned how to write, I hope to be able to write the next one much more quickly. I don’t dare give a timeline as who knows what life has in store….but it would be nice to get it done in a couple years.

13. How do you hope ‘Creature of Air and Still Water’ will resonate with readers globally?

The biggest themes in Creature of Air and Still Water are universal — healing broken families or moving on from family hurt, the complex love/hate relationship between siblings, finding your place in the world, making peace between the warring parts of yourself, being true to your calling. I hope every reader can relate to one or more of these themes and finds some useful insights or validation for their own journey. But above all, I want them to be entertained and moved, and hope they will feel the book has added a bit of beauty to their lives.

14. Any other comments you would like to add?

It would be a dream come true to see this book inspire other people to become writers, particularly Sierra Leoneans.

| Thank you for Signing Up |

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Bimbola Carrol is the founder and CEO of Visit Sierra Leone (VSL TRAVEL), a prominent destination management company in Sierra Leone. He has played a key role in promoting Sierra Leone as an up-and-coming tourist spot and fostering sustainable tourism, contributing to the country’s economy, culture, and environment. His expertise in tourism, IT, marketing, and e-commerce enables him to provide valuable services to clients. In his free time, he enjoys squash, hiking, writing and profiling innovative businesses in Sierra Leone.

Comment (0)